Friday, April 19, 2024

Friday, April 19, 2024  Friday, April 19, 2024

Friday, April 19, 2024

In cities like Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary, where condo dwellers and office-goers rely on elevators as the first and last leg of their commutes, a ride on the lift has become a risk rather than an inconvenience.

In a vertical city that boasts about how it leads the continent in active construction sites, the hundreds of thousands of Torontonians living in high-rises have been grappling with the uncomfortable reality that elevators are among the least desirable forms of transportation in a pandemic.

“That’s the most risky thing I have to do,” says Rob McLarty, a software developer who lives on the 33rd floor of a downtown condo tower, says of taking the elevator. So much so that he rarely leaves his apartment. “I’m very anxious as things start to re-open,” he says. “More people will be on the streets, in the grocery stores, and in my building…Knock on wood, I’ve been lucky I haven’t gotten sick yet.”

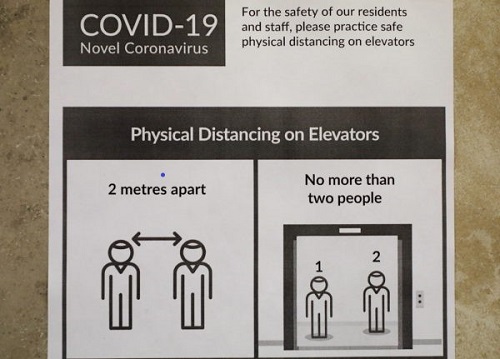

At the request of public health authorities, landlords have imposed limits on the number of people who can ride at one time; in older high-rises with cramped lifts, that number may be no more than two, which means line-ups in lobbies and testy encounters after an extra person boards instead of waiting for the next one.

The confined dimensions and limited air circulation in elevators pose the same kinds of potential health risks as do other tight indoor spaces. Richard Corsi, dean of engineering at Portland State University, worked up, and then tweeted, a theoretical estimate on how aerosol-born coronavirus might linger in an elevator after a passenger speaks or coughs. Corsi estimated that elevator air could remain infectious from viruses emitted by an asymptomatic individual riding up 10 floors, even after they’ve exited. Other experts disagree, and Corsi admits that his calculations are uncertain because much about the virus’s behaviour isn’t clear.

While the epidemiological evidence to date doesn’t specifically finger elevators as a contagion vector except in hospitals, the emerging picture of the geography of the pandemic shows that COVID-19 is far more prevalent in low-income, racialized suburban communities where residents tend to live in high-rise apartment complexes built in the 1960s and ‘70s.

This isn’t just a Toronto story. People who live in high-rise districts in Vancouver, Calgary, and Montreal are all contending with the same issues, as are people in other vertical neighbourhoods in other cities.

Check out the video gallery here